There’s something exciting about doing more with less — that’s the philosophy behind the low-power ham radio subculture known as “QRP”. Try to build the tiniest radio you can, using the least power, putting out the tiniest signal, and still use it talk to somebody across the ocean. That’s the MacGuyver thrill!

I like to be able to operate morse code when I go on business trips, or just when I’m at the park. My own search for minimalism breaks down into one central goal: how little can I carry with me, and still have a working radio station? Carrying less creates more clever thrill, but also usually means sacrificing things too. For me, my search has broken down into two parts.

The Radio

I started out with a Yaesu 817, which is a tiny radio that does everything. However, it’s quite heavy (2.6 pounds) and eats battery quickly (around 400mA just on receive!) This forced me to carry an external battery. And because I often need to tune my antenna, I had to carry an external tuner. All in all, the parts filled a camera bag by themselves.

I then moved to a ultra-minimal TenTec R4020, which was much lighter (1.1 pounds), and used its eight internal AA batteries an order of magnitude more conservatively (55mA on receive!). Of course, it lacked other options: no voice/sideband ability, cryptic controls, primitive keyer, no filtering or noise reduction, only two amateur bands, and still no tuner!

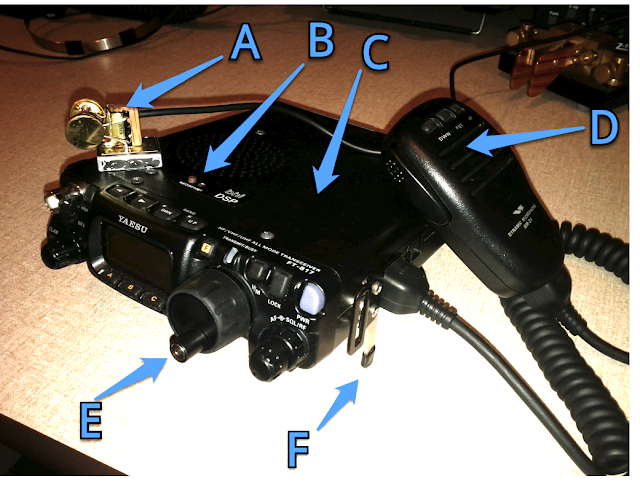

I finally settled on the Elecraft KX3, which is truly mind-blowing. With 8 AA batteries, it weighs only 1.6 pounds, has reasonable current draw (150mA receive) and is 100% software-defined radio. It operates sideband or CW on every single band, and even does digital (PSK31) right on the device. It has more digital processing and filtering options than my giant IC-7200 base station. The controls are a joy to use, with two VFOs, auto-spotting of CW signal, noise reduction, multi-memory keyer, frequency memories, …the works. I literally stopped using my base station when this radio arrived; my base station felt too primitive and limited. The killer features for me were a built-in recharger for NiMH AA cells, and a built-in tuner(!)

The Antenna

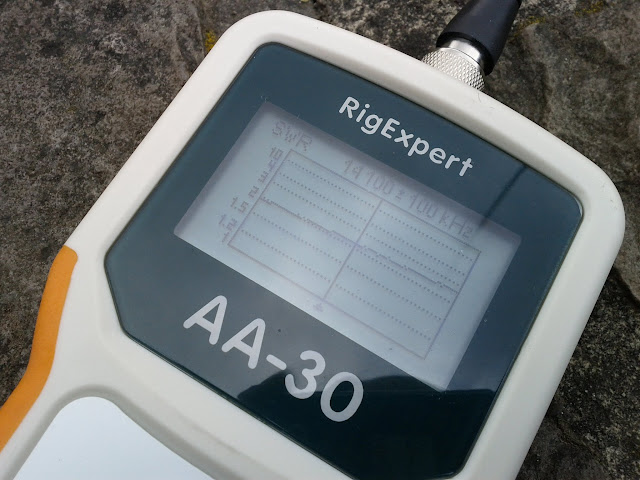

A year or two ago, it seemed necessary to lug a whole separate portable antenna “kit” wherever I went. The Buddipole was the kit, and a great kit it is. Unfortunately, it’s a pretty sizeable 2 foot long bag full of metal clanky parts: tripod, extendable mast, assembled 10′ arms, tunable coils, counterpoise wires, guying wires, etc. Plus an antenna analyzer to get the tuning just right. That’s a lot of junk to carry.

Later I pared the equipment down to a mere “Buddistick”, which is a smaller vertical version of the Buddipole: a single clamp for a railing, with a small coil and arms/whip attached, and a single counterpoise wire. This fit in a small purse-sized bag.

Then I got more minimal: a PAR “Endfedz” antenna. It’s just a 40′ antenna with LC-matching box on the tip, which plugs right into the radio. Chuck one end in a tree with a water bottle, plug the other end in. It wraps into a bundle the size of a ziploc bag. Not bad. Still a slightly bulky package, though.

Finally I noticed on Elecraft’s mailing lists that the founders/designers described their own favorite “trail friendly” antenna: nothing but a teensy 1 ounce spool (26 feet) of 26 AWG ‘silky’ wire, #534 purchased from thewireman.com, and attached to a Pomona 3430 connector. The 3430 connector allows a longwire to be directly attached to the radio’s BNC port, and a second 16 foot wire is attached as a counterpoise by wrapping around a radio chassis screw. Both spools are tiny enough to slip in my jeans pocket; they feel like nothing but a long, teflon-coated guitar string! And of course it all works because of the radio’s internal tuner — I was able to tune 17m, 20m, 30m, and sometimes 40m with these two tiny wires. Had a nice morse chat from Chicago to Alabama on only 5 watts. In the picture below, you see the longwire coiled into my palm. In the picture of the KX3, you can see the two wires attached to the radio, and how it can all nicely fit in the padded case.

This, at last, is the long wire that I can slip into the edges of the KX3 radio’s padded case — no more carrying an “antenna bag” as a second package.